Man, I hope I'm not abusing this forum with all my questions. You all are really helpful!

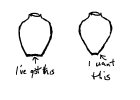

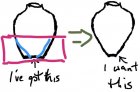

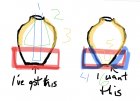

First, let me say that in the following situation, I'm turning green wood to finished dimension (1/8 to 3/16 thickness) and letting it dry as it wants to dry. I'm currently working on an end grain cherry HF that's about 13" tall by 11 inches wide. As shown in the poorly drawn attached image, my base is currently about 4 inches wide. That's primarily because my tenon is 3 1/2 inches wide with a little bit of shoulder to rest against the chuck rim. I want the base to be more narrow (more delicate looking), maybe 2 to 2 1/2 inches. Because I haven't yet hollowed it, I feel I need to leave it thicker at the base (as it is now) for stability during hollowing. If I leave it as is and account for the final base dimension while I hollow, when I let it dry, I have two problems. One is that with the half inch tenon that exist, plus the extra bulk I'd be leaving to turn off later, I feel like there is serious risk of some cracking while it dries because of the walls thickness difference (3/16 walls and an inch plus at the base). The other problem is that it's no longer going to be round when it dries due to some warping, so re-turning the thick base off is going to cause some problems.

How do you think this is best handled?

Thanks,

Grey

First, let me say that in the following situation, I'm turning green wood to finished dimension (1/8 to 3/16 thickness) and letting it dry as it wants to dry. I'm currently working on an end grain cherry HF that's about 13" tall by 11 inches wide. As shown in the poorly drawn attached image, my base is currently about 4 inches wide. That's primarily because my tenon is 3 1/2 inches wide with a little bit of shoulder to rest against the chuck rim. I want the base to be more narrow (more delicate looking), maybe 2 to 2 1/2 inches. Because I haven't yet hollowed it, I feel I need to leave it thicker at the base (as it is now) for stability during hollowing. If I leave it as is and account for the final base dimension while I hollow, when I let it dry, I have two problems. One is that with the half inch tenon that exist, plus the extra bulk I'd be leaving to turn off later, I feel like there is serious risk of some cracking while it dries because of the walls thickness difference (3/16 walls and an inch plus at the base). The other problem is that it's no longer going to be round when it dries due to some warping, so re-turning the thick base off is going to cause some problems.

How do you think this is best handled?

Thanks,

Grey